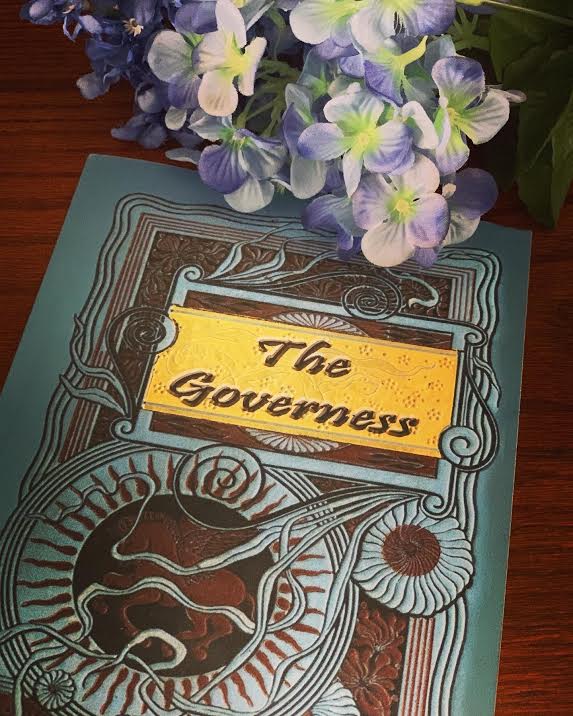

The Governess

Published in 1749 the story of Mrs. Teachum and the nine pupils who make up her “Little Female Academy” is widely recognized as the first full-length novel for children, and the first to be aimed specifically at girls.

The author Sarah Fielding’s (1710–68) aim was to provide moral instruction in an enjoyable way.

“While the novel appears conventional enough on the surface, it is, in several ways, quite subversive. Fielding includes fairy tales in her novel, a risky move at a time when people’s feelings about letting children read such fanciful text were mixed at best. As much of the novel concerns itself with the importance of learning to effectively and accurately read both texts and lives, Fielding obviously felt that her readers, and her characters, were intelligent enough to read without being overwhelmed with fanciful thoughts and desires. Ironically, the tales themselves end, not with the marriage of the hero and heroine that one might expect, but with alternate resolutions. Chloe, who had competed with her sister Caelia for the hand of Sempronius, decides to live with the couple at the end, and all three live together as one family quite happily. Likewise, Mignon described as a pretty delicate male, chooses to spend his life with a married couple. Although Fielding’s reader doesn’t encounter radically independent women in this novel, she does encounter the possibility of alternatives to the conventional marriage and family unit. As such, while the surface of the novel presents a story quite in the line with eighteenth century femininity and womanhood, the subtext presents a different vision, one that insists on personal agency and intelligence.”

From Sean Gerard Kavanagh’s excellent write up on The Governess:

“Governess: it’s no accident that the first English novel for children is a highly dialogic text, written in the historical context of a growing interest in children’s education and in children’s literature, and by an author with a vested interest in engaging with the debate on female children’s education in particular, and engaging her readers in that same debate. Indeed, without an understanding of the text’s dialogism, any reading of Governess and understanding of its legacy is diminished.”

I cannot wait to read this gem.