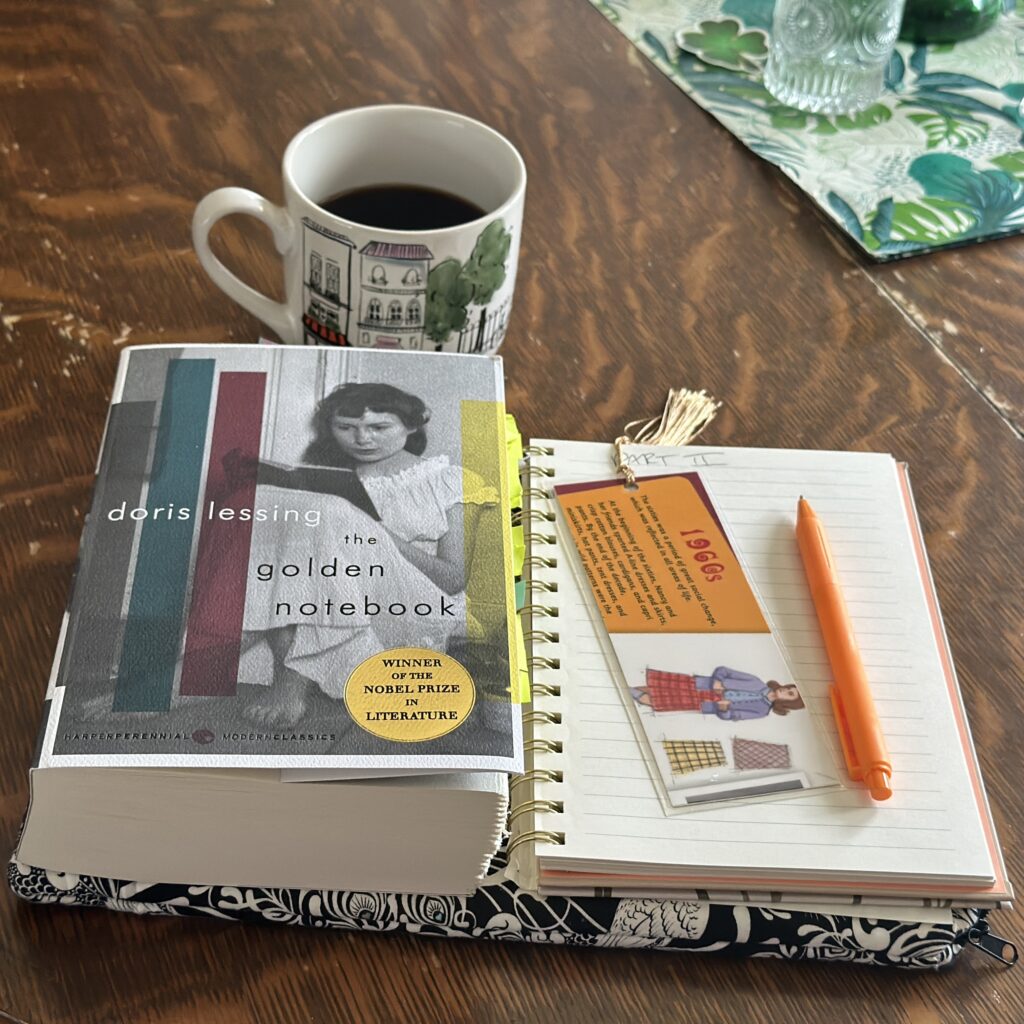

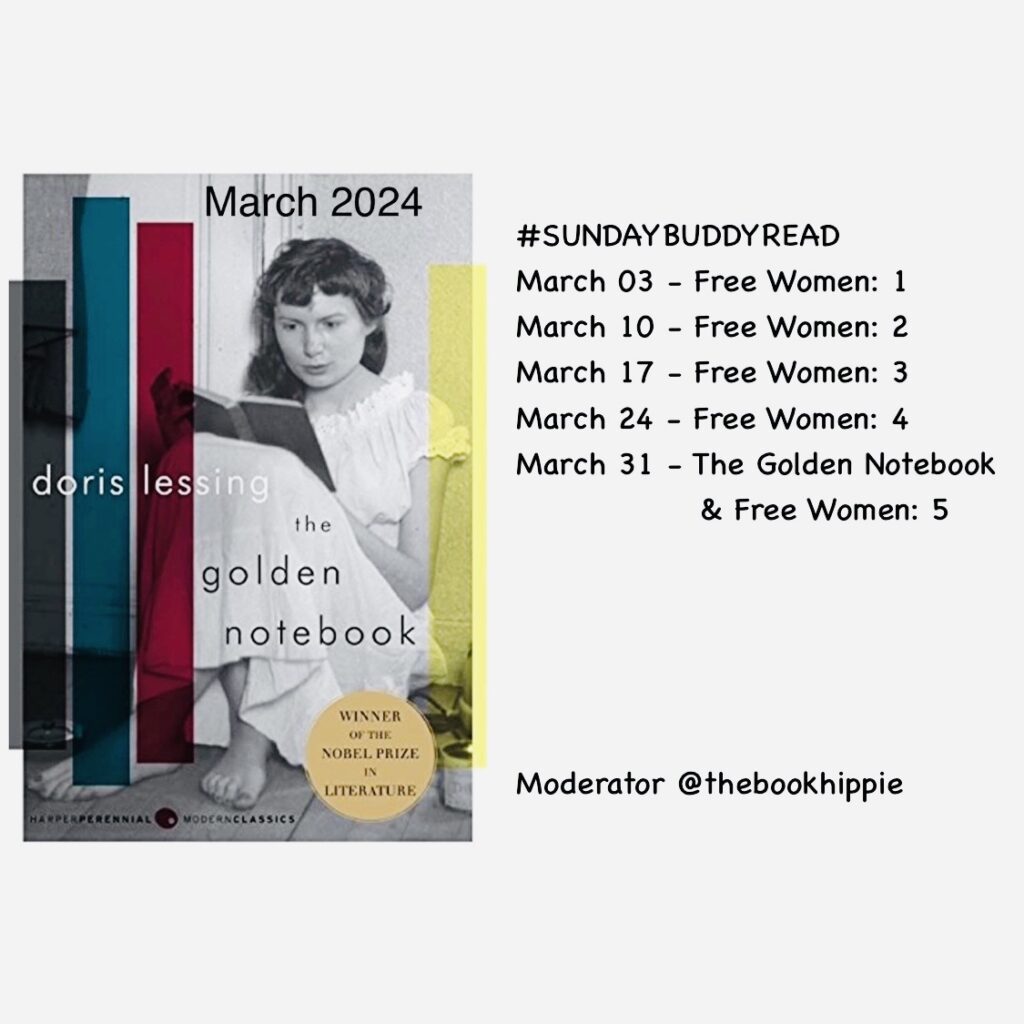

Sundays with THE GOLDEN NOTEBOOK

The Golden Notebook is a 1962 novel by the British writer Doris Lessing.

Like her two books that followed, it enters the realm of what Margaret Drabble in The Oxford Companion to English Literature called Lessing’s

“inner space fiction”; her work that explores mental and societal breakdown.

The novel contains anti-war and anti-Stalinist messages, an extended analysis of communism and the Communist Party in England from the 1930s to the 1950s, and an examination of the budding sexual revolution and women’s liberation movements.

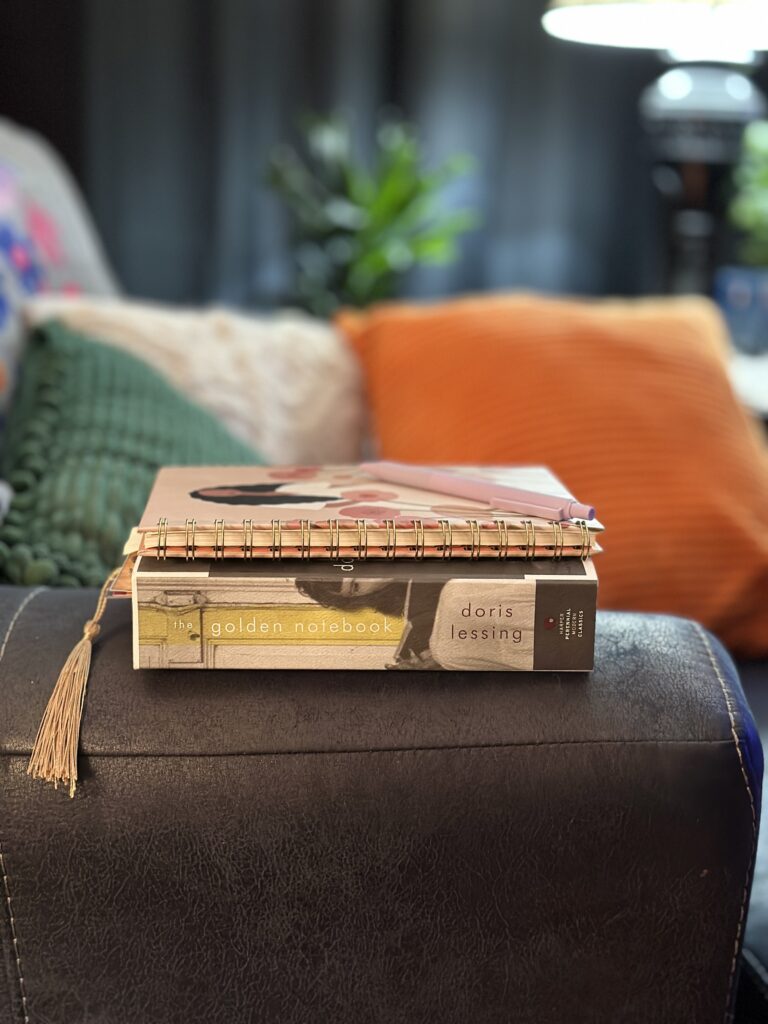

Whew. The following are SOME of my thoughts, in order, while reading. I have also filled an entire notebook …

Good book for Women’s History Month.

Lessing’s radical exploration of communism, female liberation, motherhood and mental breakdown was hailed as the ‘feminist bible’ and reviled as ‘castrating’. “ ~ The Guardian

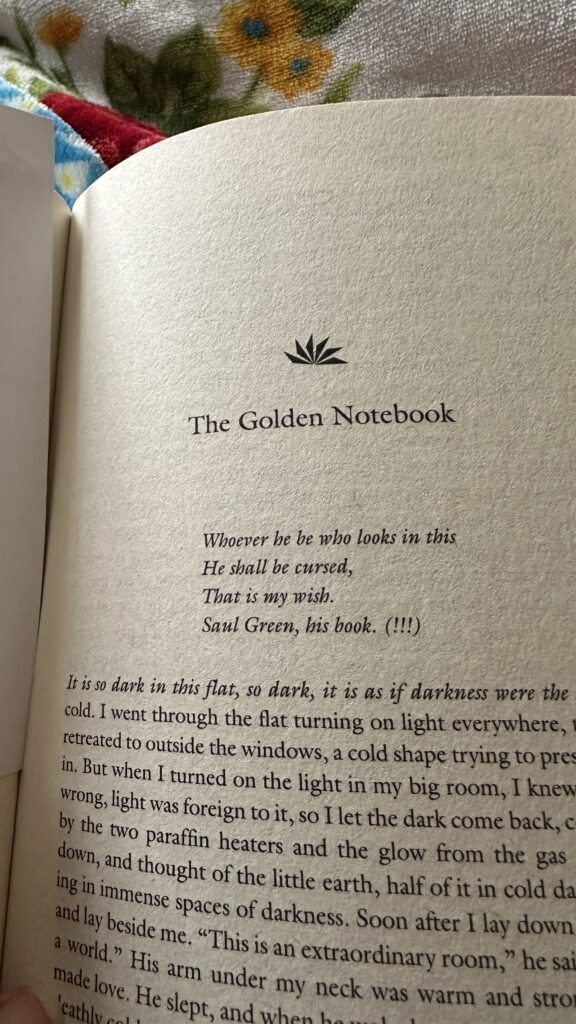

The Golden Notebook is the story of writer Anna Wulf, the four notebooks in which she records her life, and her attempt to tie them together in a fifth, gold-coloured notebook.

“The Golden Notebook is Doris Lessing’s most important work and has left its mark upon the ideas and feelings of a whole generation of women.” — New York Times Book Review

Anna is a writer, author of one very successful novel, who now keeps four notebooks. In one, with a black cover, she reviews the African experience of her earlier years. In a red one she records her political life, her disillusionment with communism. In a yellow one she writes a novel in which the heroine relives part of her own experience. And in a blue one she keeps a personal diary. Finally, in love with an American writer and threatened with insanity, Anna resolves to bring the threads of all four books together in a golden notebook.

Lessing’s best-known and most influential novel, The Golden Notebook retains its extraordinary power and relevance decades after its initial publication.

“I can’t understand how anyone can see what’s happening to this country and not hate it, on the surface everything is fine -all quiet and tame and stubborn, but underneath it’s poisonous it’s full of hatred and envy and people being lonely.”

The Golden Notebook is a 1962 novel by the British writer Doris Lessing. 1962!!!!!!!!!

On to part two. So far, I’m intrigued. I’m also struck by the similarities to today. Especially concerning Russia, China, Education, Feminism, Racism, Classism and Communism. Nothing new under the sun. Our current backslide is horrific, and frightening.

The Golden Notebook is the story of writer Anna Wulf, the four notebooks in which she records her life, and her attempt to tie them together in a fifth, gold-coloured notebook.

‘Last night I was at a meeting which went on till nearly morning.

Towards the end a man who had not spoken before, a socialist from Austria, made a short humorous speech, something like this: “My dear Comrades. I have been listening to you, amazed at the wells of faith in human beings! What you are saying amounts to this: that you know the leadership of the British C.P. consists of men and women totally corrupted by years of work in the Stalinist atmosphere. You know they will do anything to maintain their position. You know, because you have given a hundred examples of it here this evening, that they suppress resolutions, rig ballots, pack meetings, lie and twist.

There is no way of getting them out of office by democratic means partly because they are unscrupulous, and partly because half of the Party members are too innocent to believe their leaders are capable of such trickery. But every time you reach this point in your deliberations you stop, and instead of drawing the obvious conclusions from what you have said, you go off into some day-dream and talk as if all you have to do is to appeal to the leading comrades to resign all at once because it would be in the best interests of the Party if they did. It is as if you proposed to appeal to a professional burglar to retire because his efficiency was giving his profession a bad name.” ‘

C.P. = Communist Party

(Pg 427-428)

1962 this book was published . THAT FACT is blowing my mind….

“I am very interested in the growth of communities founded on religious principles that’s happening now because I’ve got a feeling that that is where the next ideology will come from.”

Q: Are there any political ideologies worth believing in today?

A: I don’t think so. I just don’t like these big ideas because I’ve seen what happens to them. What I do think is worthwhile is the smaller objective, because that can’t be overtaken by some lunatic or other. But there is a great vacuum at the moment. I am very interested in the growth of communities founded on religious principles that’s happening now because I’ve got a feeling that that is where the next ideology will come from. In terms of my lot, however, I think we’re immune. Or I hope that we are.Q: Do you worry that younger generations are so apathetic?

A: No, not at all—at least you’re not talking rubbish about the Soviet Union! I think it’s rather healthy. But there is a vacuum. I can easily imagine a charismatic chap sweeping you all away… and you wouldn’t realize.Q: You’ve lived through one of the most tumultuous centuries in our history.

How has that affected you?

A: Well, I’ve lived through Hitler, ranting and raving; Mussolini too; the Soviet Union, which we thought would last for all time; the British Empire, which seemed impregnable; the color bar in Rhodesia and elsewhere; the heyday of European empires.

It was inconceivable to think these would disappear. They seemed permanent. Now not one of them remains and I think that that is a recipe for optimism!~ interview with Doris Lessing by Sarah O’Reilly

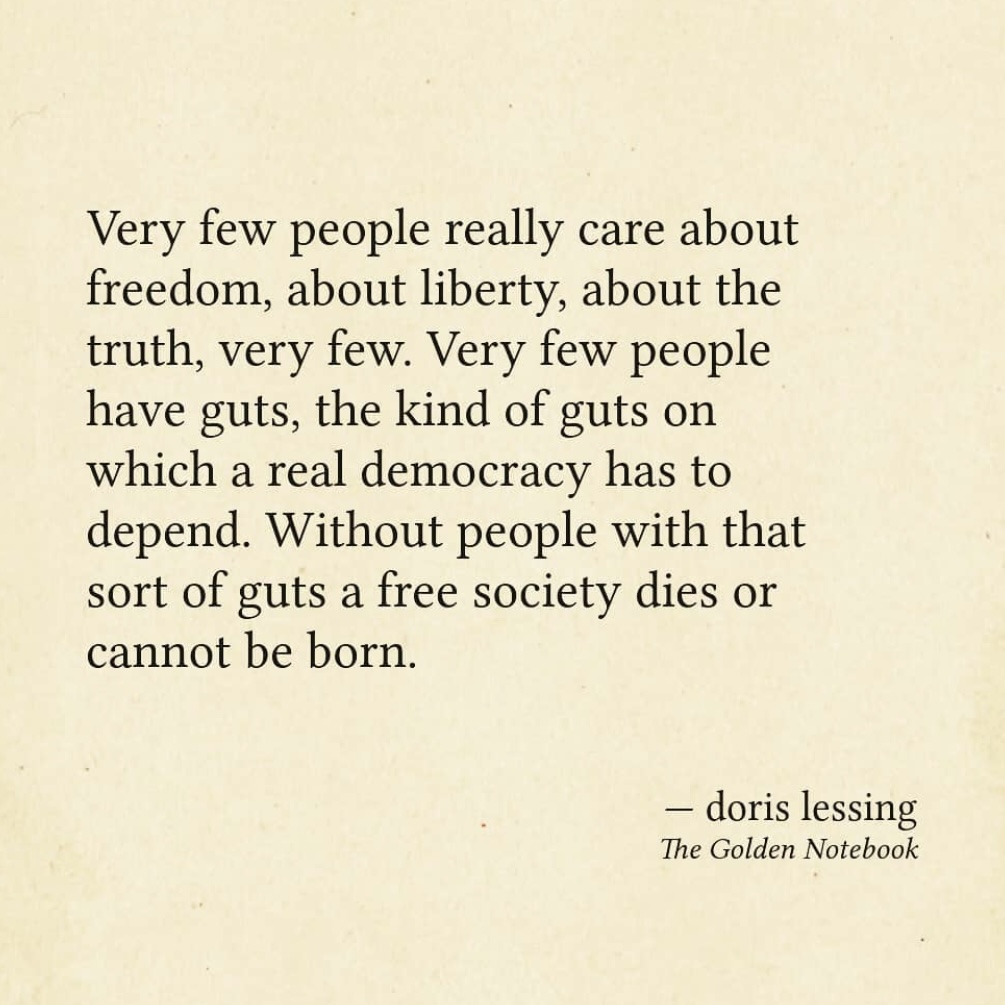

662 pages later and I’ve finished The Golden Notebook. It is, by some, a feminist must read, notsomuch. Although it’ll definitely make you see what it’s like to have no rights and be property, chattel… oh wait. The author was quite upset this was seen as a feminist book. She was more proud of the style of writing. She was observing what happens when all your ideology dies and regimes fall and the very thing you thought was everything -your core of beliefs and political leanings – is in fact false.

It was work. I am glad I read it. Some prose took my breath away.

“The Golden Notebook is Doris Lessing’s most important work and has left its mark upon the ideas and feelings of a whole generation of women.” — New York Times Book Review

Anna is a writer, author of one very successful novel, who now keeps four notebooks. In one, with a black cover, she reviews the African experience of her earlier years. In a red one she records her political life, her disillusionment with communism. In a yellow one she writes a novel in which the heroine relives part of her own experience. And in a blue one she keeps a personal diary. Finally, in love with an American writer and threatened with insanity, Anna resolves to bring the threads of all four books together in a golden notebook.

Lessing’s best-known and most influential novel, The Golden Notebook retains its extraordinary power and relevance decades after its initial publication.

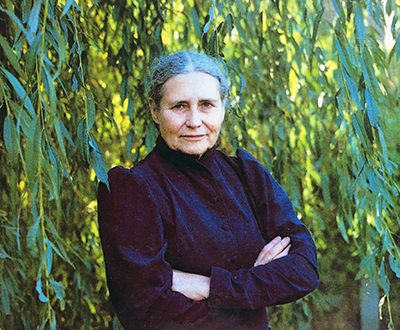

Biography

From the pamphlet:

A Reader’s Guide to The Golden Notebook & Under My Skin,

HarperPerennial, 1995

| Doris Lessing was born Doris May Tayler in Persia (now Iran) on October 22, 1919. Both of her parents were British: her father, who had been crippled in World War I, was a clerk in the Imperial Bank of Persia; her mother had been a nurse. In 1925, lured by the promise of getting rich through maize farming, the family moved to the British colony in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Doris’s mother adapted to the rough life in the settlement, energetically trying to reproduce what was, in her view, a civilized, Edwardian life among savages; but her father did not, and the thousand-odd acres of bush he had bought failed to yield the promised wealth.Lessing has described her childhood as an uneven mix of some pleasure and much pain. The natural world, which she explored with her brother, Harry, was one retreat from an otherwise miserable existence. Her mother, obsessed with raising a proper daughter, enforced a rigid system of rules and hygiene at home, then installed Doris in a convent school, where nuns terrified their charges with stories of hell and damnation. Lessing was later sent to an all-girls high school in the capital of Salisbury, from which she soon dropped out. She was thirteen; and it was the end of her formal education. But like other women writers from southern African who did not graduate from high school (such as Olive Schreiner and Nadine Gordimer), Lessing made herself into a self-educated intellectual. She recently commented that unhappy childhoods seem to produce fiction writers. “Yes, I think that is true. Though it wasn’t apparent to me then. Of course, I wasn’t thinking in terms of being a writer then – I was just thinking about how to escape, all the time.” The parcels of books ordered from London fed her imagination, laying out other worlds to escape into. Lessing’s early reading included Dickens, Scott, Stevenson, Kipling; later she discovered D.H. Lawrence, Stendhal, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky. Bedtime stories also nurtured her youth: her mother told them to the children and Doris herself kept her younger brother awake, spinning out tales. Doris’s early years were also spent absorbing her father’s bitter memories of World War I, taking them in as a kind of “poison.” “We are all of us made by war,” Lessing has written, “twisted and warped by war, but we seem to forget it.” In flight from her mother, Lessing left home when she was fifteen and took a job as a nursemaid. Her employer gave her books on politics and sociology to read, while his brother-in-law crept into her bed at night and gave her inept kisses. During that time she was, Lessing has written, “in a fever of erotic longing.” Frustrated by her backward suitor, she indulged in elaborate romantic fantasies. She was also writing stories, and sold two to magazines in South Africa. Lessing’s life has been a challenge to her belief that people cannot resist the currents of their time, as she fought against the biological and cultural imperatives that fated her to sink without a murmur into marriage and motherhood. “There is a whole generation of women,” she has said, speaking of her mother’s era, “and it was as if their lives came to a stop when they had children. Most of them got pretty neurotic – because, I think, of the contrast between what they were taught at school they were capable of being and what actually happened to them.” Lessing believes that she was freer than most people because she became a writer. For her, writing is a process of “setting at a distance,” taking the “raw, the individual, the uncriticized, the unexamined, into the realm of the general.” In 1937 she moved to Salisbury, where she worked as a telephone operator for a year. At nineteen, she married Frank Wisdom, and had two children. A few years later, feeling trapped in a persona that she feared would destroy her, she left her family, remaining in Salisbury. Soon she was drawn to the like-minded members of the Left Book Club, a group of Communists “who read everything, and who did not think it remarkable to read.” Gottfried Lessing was a central member of the group; shortly after she joined, they married and had a son. During the postwar years, Lessing became increasingly disillusioned with the Communist movement, which she left altogether in 1954. By 1949, Lessing had moved to London with her young son. That year, she also published her first novel, The Grass Is Singing, and began her career as a professional writer. Lessing’s fiction is deeply autobiographical, much of it emerging out of her experiences in Africa. Drawing upon her childhood memories and her serious engagement with politics and social concerns, Lessing has written about the clash of cultures, the gross injustices of racial inequality, the struggle among opposing elements within an individuals own personality, and the conflict between the individual conscience and the collective good. Her stories and novellas set in Africa, published during the fifties and early sixties, decry the dispossession of black Africans by white colonials, and expose the sterility of the white culture in southern Africa. In 1956, in response to Lessing’s courageous outspokenness, she was declared a prohibited alien in both Southern Rhodesia and South Africa. Over the years, Lessing has attempted to accommodate what she admires in the novels of the nineteenth century – their “climate of ethical judgement” – to the demands of twentieth-century ideas about consciousness and time. After writing the Children of Violence series (1951-1959), a formally conventional bildungsroman (novel of education) about the growth in consciousness of her heroine, Martha Quest, Lessing broke new ground with The Golden Notebook (1962), a daring narrative experiment, in which the multiple selves of a contemporary woman are rendered in astonishing depth and detail. Anna Wulf, like Lessing herself, strives for ruthless honesty as she aims to free herself from the chaos, emotional numbness, and hypocrisy afflicting her generation. Attacked for being “unfeminine” in her depiction of female anger and aggression, Lessing responded, “Apparently what many women were thinking, feeling, experiencing came as a great surprise.” As at least one early critic noticed, Anna Wulf “tries to live with the freedom of a man” – a point Lessing seems to confirm: “These attitudes in male writers were taken for granted, accepted as sound philosophical bases, as quite normal, certainly not as woman-hating, aggressive, or neurotic.” In the 1970s and 1980s, Lessing began to explore more fully the quasi-mystical insight Anna Wulf seems to reach by the end of The Golden Notebook. Her “inner-space fiction” deals with cosmic fantasies (Briefing for a Descent into Hell, 1971), dreamscapes and other dimensions (Memoirs of a Survivor, 1974), and science fiction probings of higher planes of existence (Canopus in Argos: Archives, 1979-1983). These reflect Lessing’s interest, since the 1960s, in Idries Shah, whose writings on Sufi mysticism stress the evolution of consciousness and the belief that individual liberation can come about only if people understand the link between their own fates and the fate of society.Lessing’s other novels include The Good Terrorist (1985) and The Fifth Child (1988); she also published two novels under the pseudonym Jane Somers (The Diary of a Good Neighbour, 1983 and If the Old Could…, 1984). In addition, she has written several nonfiction works, including books about cats, a love since childhood. Under My Skin: Volume One of My Autobiography, to 1949 appeared in 1995 and received the James Tait Black Prize for best biography. Addenda (by Jan Hanford)In June 1995 she received an Honorary Degree from Harvard University. Also in 1995, she visited South Africa to see her daughter and grandchildren, and to promote her autobiography. It was her first visit since being forcibly removed in 1956 for her political views. Ironically, she is welcomed now as a writer acclaimed for the very topics for which she was banished 40 years ago. She collaborated with illustrator Charlie Adlard to create the unique and unusual graphic novel, Playing the Game. After being out of print in the U.S. for more than 30 years, Going Home and In Pursuit of the English were republished by HarperCollins in 1996. These two fascinating and important books give rare insight into Mrs. Lessing’s personality, life and views. In 1996, her first novel in 7 years, Love Again, was published by HarperCollins. She did not make any personal appearances to promote the book. In an interview she describes the frustration she felt during a 14-week worldwide tour to promote her autobiography: “I told my publishers it would be far more useful for everyone if I stayed at home, writing another book. But they wouldn’t listen. This time round I stamped my little foot and said I would not move from my house and would do only one interview.” And the honors keep on coming: she was on the list of nominees for the Nobel Prize for Literature and Britain’s Writer’s Guild Award for Fiction in 1996. Late in the year, HarperCollins published Play with A Tiger and Other Plays, a compilation of 3 of her plays: Play with a Tiger, The Singing Door and Each His Own Wilderness. In an unexplained move, HarperCollins only published this volume in the U.K. and it is not available in the U.S., to the disappointment of her North American readers. In 1997 she collaborated with Philip Glass for the second time, providing the libretto for the opera “The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five” which premiered in Heidelberg, Germany in May. Walking in the Shade, the anxiously awaited second volume of her autobiography, was published in October and was nominated for the 1997 National Book Critics Circle Award in the biography/autobiography category. This volume documents her arrival in England in 1949 and takes us up to the publication of The Golden Notebook. This is the final volume of her autobiography, she will not be writing a third volume. Her new novel, titled “Mara and Dann”, was been published in the U.S in January 1999 and in the U.K. in April 1999. In an interview in the London Daily Telegraph she said, “I adore writing it. I’ll be so sad when it’s finished. It’s freed my mind.” In May 1999 she will be presented with the XI Annual International Catalunya Award, an award by the government of Catalunya. December 31 1999: In the U.K.’s last Honours List before the new Millennium, Doris Lessing was appointed a Companion of Honour, an exclusive order for those who have done “conspicuous national service.” She revealed she had turned down the offer of becoming a Dame of the British Empire because there is no British Empire. Being a Companion of Honour, she explained, means “you’re not called anything – and it’s not demanding. I like that”. Being a Dame was “a bit pantomimey”. The list was selected by the Labor Party government to honor people in all walks of life for their contributions to their professions and to charity. It was officially bestowed by Queen Elizabeth II. In January, 2000 the National Portrait Gallery in London unveiled Leonard McComb’s portrait of Doris Lessing. Ben, in the World, the sequel to The Fifth Child was published in Spring 2000 (U.K.) and Summer 2000 (U.S.). In 2001 she was awarded the Prince of Asturias Prize in Literature, one of Spain’s most important distinctions, for her brilliant literary works in defense of freedom and Third World causes. She also received the David Cohen British Literature Prize. She was on the shortlist for the first Man Booker International Prize in 2005. In 2007 she was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. Her final novel was Alfred and Emily. She died on November 17, 2013. |