Mine Eyes Have Seen is a play by Alice Dunbar Nelson. It was published in the April 1918 edition of the monthly news magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People entitled The Crisis. The play is an examination on the nature of patriotism, citizenship, sacrifice and what those mean for people who have been betrayed by their own country.

Black, bisexual feminist Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson – Poet, essayist, diarist, and activist Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, to mixed-race parents. Her African American, Anglo, Native American, and Creole heritage contributed to her complex understandings of gender, race, and ethnicity, subjects she often addressed in her work. She graduated from Straight University (now Dillard University) and taught in the New Orleans public schools. Her first book, Violets and Other Tales (1895), was published when she was just 20. Her second collection, The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories (1899) explored the lives of creole and anglicized characters. Works exploring racism and racial oppression were largely rejected by publishers during her lifetime, a situation which, according to Sheila Smith McKoy, “made it difficult for both readers and critics to access Dunbar-Nelson’s work.”

A writer of short stories, essays, and poems, Dunbar-Nelson was comfortable in many genres but was best known for her prose. One of the few female African American diarists of the early 20th century, she portrays the complicated reality of African American women and intellectuals, addressing topics such as racism, oppression, family, work, and sexuality. According to Gloria T. Hull, “Dunbar-Nelson perforce wrote in the interstices of a busy existence unsupported (except for one brief period) by any of the money or leisure traditionally associated with people of letters. Doggedly determined to be an author, she plied her trade… carried forward on the flow of words that came quite easily for her. Interestingly enough, she called all of her writing ‘producing literature,’ in a humorously ironic leveling of forms and types. But just as ironically, her status is lowered since the more belletristic genres of poetry and fiction are more valued than the noncanonical forms—notably the diary and journalistic essay—that claimed so much of her attention.” Hull edited the volume Give Us Each Day: The Diary of Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1984).

In 1898 she married the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar; they separated in 1902, and Dunbar-Nelson moved to Wilmington, Delaware. She taught at Howard High School, the State College for Colored Students (now Delaware State College), and Howard University, and she continued to publish essays, poetry, and newspaper articles. She married Arthur Callis in 1910, though the couple also divorced. Coeditor of A.M.E Reivew in these years, Dunbar-Nelson also published Masterpieces of Negro Eloquence (1914).

Dunbar-Nelson was politically active, organizing for the women’s suffrage movement in the mid-Atlantic states and acting as field representative for the Woman’s Committee of the Council of Defense in 1918; she also campaigned for the passage of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill of 1924. In 1916 she married Robert J. Nelson. In her later years she published poetry in Black newspapers such as the Crisis, Ebony and Topaz, and Opportunity. She also edited The Dunbar Speaker and Entertainer (1920) and, with Nelson, coedited the Wilmington Advocate. She died in Philadelphia.

I Sit and Sew

I sit and sew—a useless task it seems,

My hands grown tired, my head weighed down with dreams—

The panoply of war, the martial tred of men,

Grim-faced, stern-eyed, gazing beyond the ken

Of lesser souls, whose eyes have not seen Death

Nor learned to hold their lives but as a breath—

But—I must sit and sew.

I sit and sew—my heart aches with desire—

That pageant terrible, that fiercely pouring fire

On wasted fields, and writhing grotesque things

Once men. My soul in pity flings

Appealing cries, yearning only to go

There in that holocaust of hell, those fields of woe—

But—I must sit and sew.

The little useless seam, the idle patch;

Why dream I here beneath my homely thatch,

When there they lie in sodden mud and rain,

Pitifully calling me, the quick ones and the slain?

You need, me, Christ! It is no roseate seam

That beckons me—this pretty futile seam,

It stifles me—God, must I sit and sew?

This poem is in the public domain.

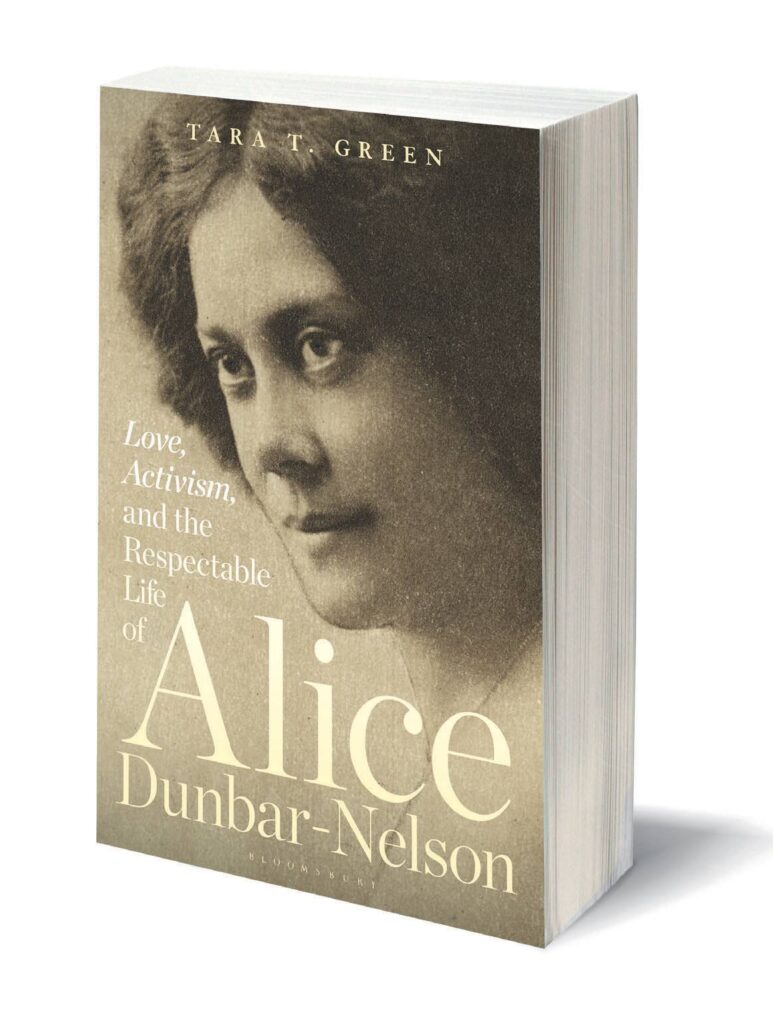

Love, Activism, and the Respectable Life of Alice Dunbar-Nelson (2022) by Tara T. Green, Ph.D. is the only existing biography of the pioneering Black activist, writer, suffragist and educator who spent three decades helping to shape Black life and politics in Wilmington and beyond.

About a decade ago, Green visited the University of Delaware library to research Dunbar-Nelson. “I thought I’d get a few boxes,” Green remembers. But the librarian ultimately brought her 120 volumes of archival content. “She looked at me and said, ‘What do you plan on doing with this?’” Green recalls. “I told her, ‘I don’t know,’ but in my head I heard a voice saying, ‘This is going to be a biography.’”Dunbar-Nelson connects with people across spectrums and borders, Green says. She is celebrated for her poetry and short fiction; for her influential work as an early Black journalist; for her fights for racial equality and for suffrage; and for her calls for political and educational reform. She’s also included in the canon of studies of LGBTQ writers.

But for Delawareans, her legacy is in nearly 20 years of visionary Black education as a beloved teacher at Howard High School, from about 1902 to 1920. “Howard was such an important school because it gave Black people access to education,” Green explains. “Alice was… instrumental in its growth.” Green notes that Dunbar-Nelson was also a teacher at DSU’s predecessor, the State College for Colored Students.

Also living in the civic heartbeat of Black Wilmington, the teacher-activist co-founded the city’s chapter of the NAACP, which is still active, Green says. “She shows up in the early 1900s and doesn’t leave until the 1930s—that’s a long time for a person to be somewhere.… Her imprint is everywhere, even if people don’t know her name. My hope is that will change and her story gets told.”

Another book added to the list!