To have discovered the black tulip, to have seen it for a moment… then to lose it, to lose it forever!’

Cornelius von Baerle, a respectable tulip-grower, lives only to cultivate the elusive black tulip and win a magnificent prize for its creation. But after his powerful godfather is assassinated, the unwitting Cornelius becomes caught up in deadly political intrigue and is falsely accused of high treason by a bitter rival. Condemned to life imprisonment, his only comfort is Rosa, the jailer’s beautiful daughter, and together they concoct a plan to grow the black tulip in secret.

Dumas’ last major historical novel is a tale of romantic love, jealousy and obsession, interweaving historical events surrounding the brutal murders of two Dutch statesman in 1672 with the phenomenon of tulipomania that gripped seventeenth-century Holland.

I enjoyed this Dumas and it is now my favorite of his writings. I went into it with zero expectations and I very much was surprised with the ease at which I read it.

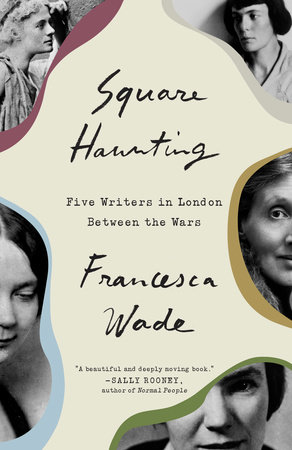

In the early twentieth century, Mecklenburgh Square—a hidden architectural gem in the heart of London—was a radical address. On the outskirts of Bloomsbury known for the eponymous group who “lived in squares, painted in circles, and loved in triangles,” the square was home to students, struggling artists, and revolutionaries.

In the pivotal era between the two world wars, the lives of five remarkable women intertwined at this one address: modernist poet H. D., detective novelist Dorothy L. Sayers, classicist Jane Harrison, economic historian Eileen Power, and author and publisher Virginia Woolf. In an era when women’s freedoms were fast expanding, they each sought a space where they could live, love, and—above all—work independently.

With sparkling insight and a novelistic style, Francesca Wade sheds new light on a group of artists and thinkers whose pioneering work would enrich the possibilities of women’s lives for generations to come.

Square Haunting

I started this book several times and just couldn’t get into it, which I believe is me and not the book. I will pick it up another time when hopefully the world isn’t a dumpster fire and my mind is quieter.

Quackery was so bizarre and freaky! I was purely fascinated and horrified.. What a read!

What won’t we try in our quest for perfect health, beauty, and the fountain of youth?

Well, just imagine a time when doctors prescribed morphine for crying infants. When liquefied gold was touted as immortality in a glass. And when strychnine—yes, that strychnine, the one used in rat poison—was dosed like Viagra.

Looking back with fascination, horror, and not a little dash of dark, knowing humor, Quackery recounts the lively, at times unbelievable, history of medical misfires and malpractices. Ranging from the merely weird to the outright dangerous, here are dozens of outlandish, morbidly hilarious “treatments”—conceived by doctors and scientists, by spiritualists and snake oil salesmen (yes, they literally tried to sell snake oil)—that were predicated on a range of cluelessness, trial and error, and straight-up scams. With vintage illustrations, photographs, and advertisements throughout, Quackery seamlessly combines macabre humor with science and storytelling to reveal an important and disturbing side of the ever-evolving field of medicine.

The Gambler Wife

In the fall of 1866, a twenty-year-old stenographer named Anna Snitkina applied for a position with a writer she idolized: Fyodor Dostoyevsky. A self-described “girl of the sixties,” Snitkina had come of age during Russia’s first feminist movement, and Dostoyevsky—a notorious radical turned acclaimed novelist—had impressed the young woman with his enlightened and visionary fiction. Yet in person she found the writer “terribly unhappy, broken, tormented,” weakened by epilepsy, and yoked to a ruinous gambling addiction. Alarmed by his condition, Anna became his trusted first reader and confidante, then his wife, and finally his business manager—launching one of literature’s most turbulent and fascinating marriages.

The Gambler Wife offers a fresh and captivating portrait of Anna Dostoyevskaya, who reversed the novelist’s freefall and cleared the way for two of the most notable careers in Russian letters—her husband’s and her own. Drawing on diaries, letters, and other little-known archival sources, Andrew Kaufman reveals how Anna protected her family from creditors, demanding in-laws, and her greatest romantic rival, through years of penury and exile. We watch as she navigates the writer’s self-destructive binges in the casinos of Europe—even hazarding an audacious turn at roulette herself—until his addiction is conquered. And, finally, we watch as Anna frees her husband from predatory contracts by founding her own publishing house, making Anna the first solo female publisher in Russian history.

The result is a story that challenges ideas of empowerment, sacrifice, and female agency in nineteenth-century Russia—and a welcome new appraisal of an indomitable woman whose legacy has been nearly lost to literary history.

I need to own this now. It is very good and I want to reread it in a much slower fashion to soak in it much longer than the time I had with a library book.

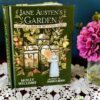

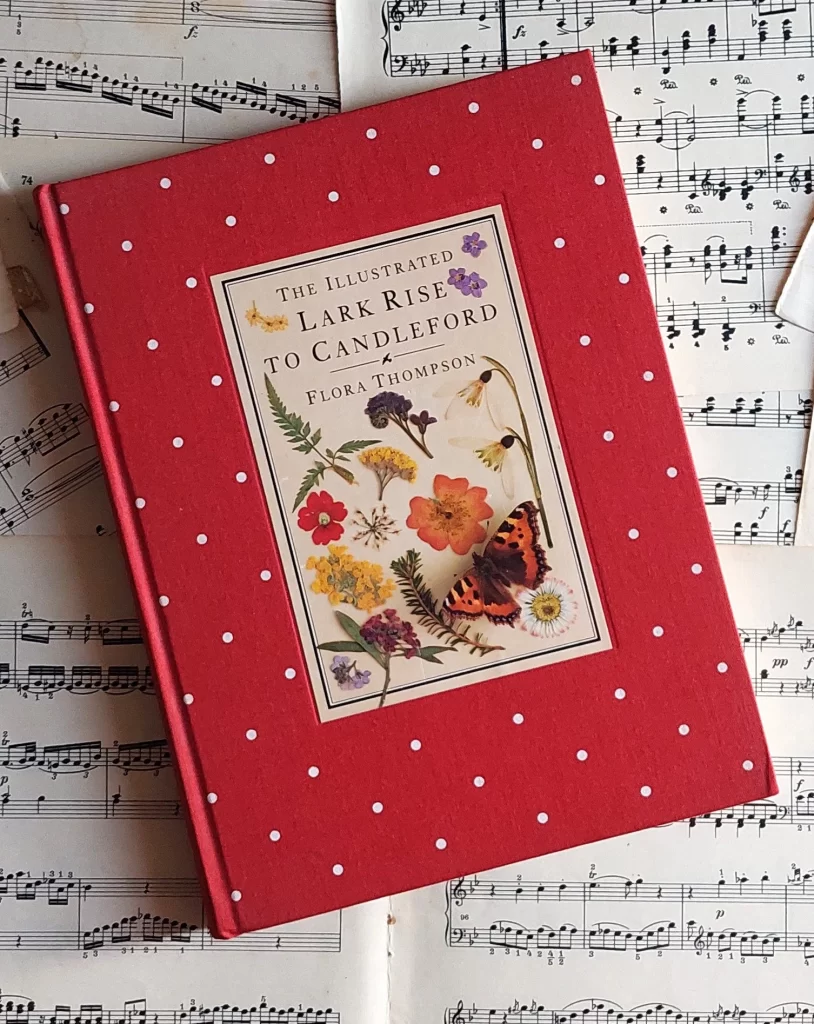

Another book I need to own. Just stunningly gorgeous and really really a pretty book.

Autobiographical accounts of country life in late nineteenth-century England, chronicle the disappearing traditions and values of hamlet, village, and small market towns…

These as previously posted were just excellent! Cookbooks are ZEN.

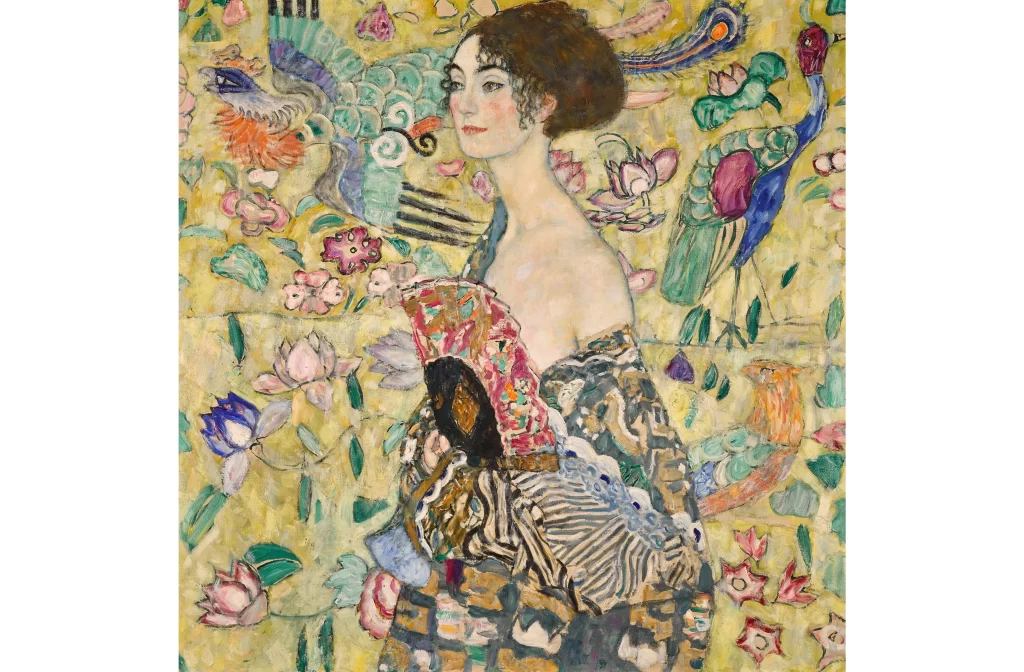

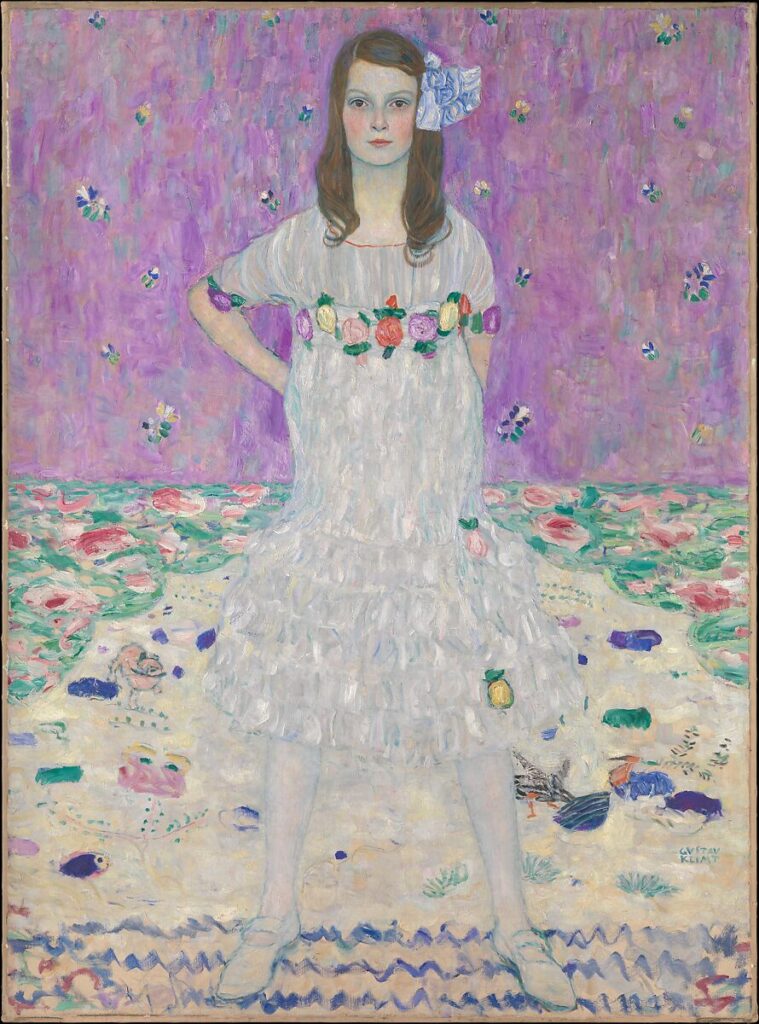

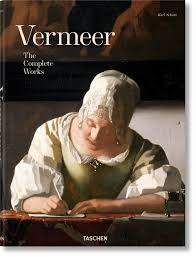

ART. I take art books out frequently from the library and I highly recommend it for everyone. I love Klimt and appreciate Vermeer.

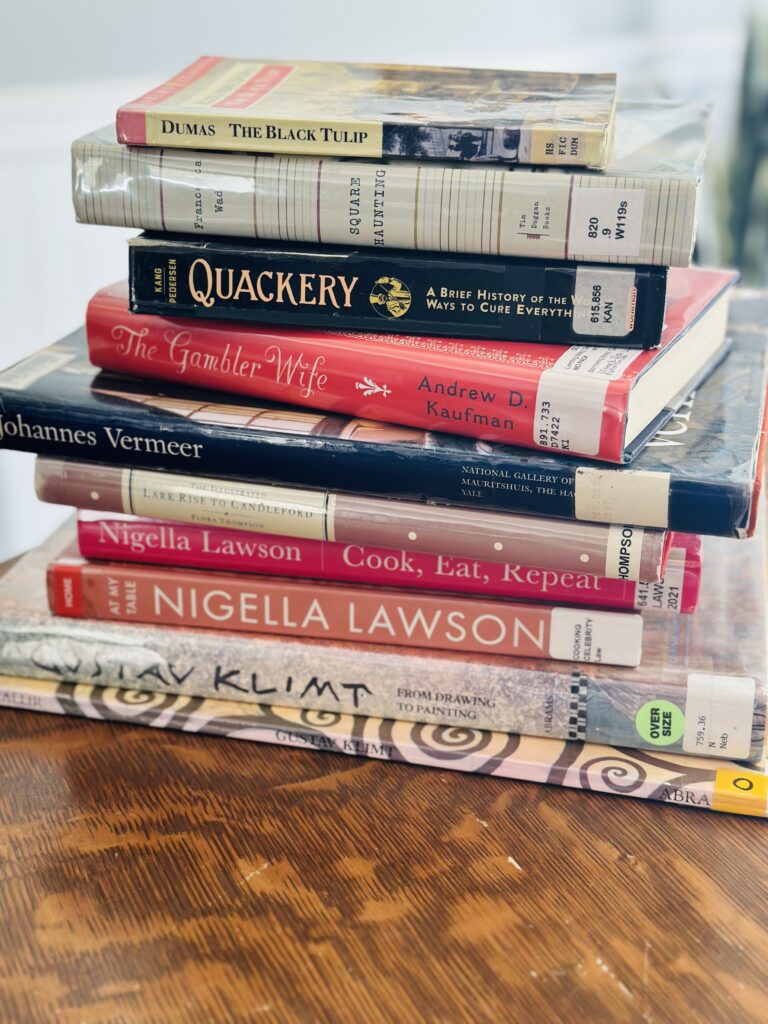

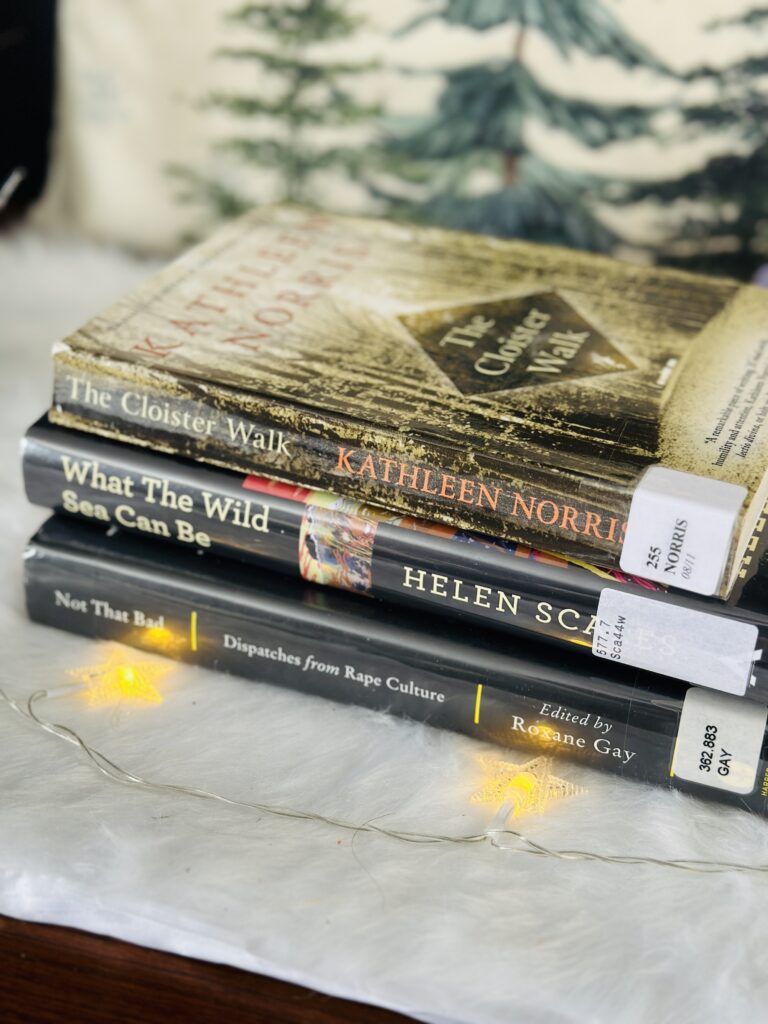

The current to be read library stack.

One for Nun lit group,

one for Author a Month

and one for Nature reading group.

Why would a married woman with a thoroughly Protestant background and often more doubt than faith be drawn to the ancient practice of monasticism, to a community of celibate men whose days are centered around a rigid schedule of prayer, work, and scripture? This is the question that poet Kathleen Norris asks us as, somewhat to her own surprise, she found herself on two extended residencies at St. John’s Abbey in Minnesota. Part record of her time among the Benedictines, part meditation on various aspects of monastic life, The Cloister Walk demonstrates, from the rare perspective of someone who is both an insider and outsider, how immersion in the cloistered world — its liturgy, its ritual, its sense of community — can impart meaning to everyday events and deepen our secular lives. In this stirring and lyrical work, the monastery, often considered archaic or otherworldly, becomes immediate, accessible, and relevant to us, no matter what our faith may be.

From the acclaimed marine biologist and author of The Brilliant Abyss , an impassioned examination of the existential threats to the world’s ocean and cautious optimism for the abundant life within it over the course of the 21st century No matter where we live, “we are all ocean people,” Helen Scales emphatically observes in her bracing yet hopeful exploration of the future of the ocean. Beginning with its fascinating deep history, Scales links past to present to show how the prehistoric ocean ecology was already working in ways similar to the ocean of today. In elegant, evocative prose, she takes readers into the realms of animals that epitomize today’s increasingly challenging conditions. Ocean life everywhere is on the move as seas warm, and warm waters are an existential threat to emperor penguins, whose mating grounds in Antarctica are collapsing. Shark populations—critical to balanced ecosystems—have shrunk by 71 per cent since the 1970s, largely the result of massive and oft-unregulated industrial fishing. Orcas—the apex predators—have also drastically declined, victims of toxic chemicals and plastics with long half-lives that disrupt the immune system and the ability to breed. Yet despite these threats, many hopeful signs remain. Increasing numbers of no-fish zones around the world are restoring once-diminishing populations. Astonishing giant kelp and sea grass forests, rivaling those on land, are being regenerated and expanded. They may be our best defense against the storm surges caused by global warming, while efforts to reengineer coral reefs for a warmer world are growing. Offering innovative ideas for protecting coastlines and cleaning the toxic seas, Scales insists we need more ethical and sustainable fisheries and must prevent the other existential threat of deep-sea mining, which could significantly alter life on earth. Inspiring us all to maintain a sense of awe and wonder at the majesty beneath the waves, she urges us to fight for the better future that still exists for the Anthropocene ocean.

In this valuable and revealing anthology, cultural critic and bestselling author Roxane Gay collects original and previously published pieces that address what it means to live in a world where women have to measure the harassment, violence, and aggression they face, and where they are “routinely second-guessed, blown off, discredited, denigrated, besmirched, belittled, patronized, mocked, shamed, gaslit, insulted, bullied” for speaking out. Contributions include essays from established and up-and-coming writers, performers, and critics, including actors Ally Sheedy and Gabrielle Union and writers Amy Jo Burns, Lyz Lenz, Claire Schwartz, and Bob Shacochis. Covering a wide range of topics and experiences, from an exploration of the rape epidemic embedded in the refugee crisis to first-person accounts of child molestation, this collection is often deeply personal and is always unflinchingly honest. Like Rebecca Solnit’s Men Explain Things to Me, Not That Bad will resonate with every reader, saying “something in totality that we cannot say alone.” Searing and heartbreakingly candid, this provocative collection both reflects the world we live in and offers a call to arms insisting that “not that bad” must no longer be good enough.

Started decorating for Cupid’s holiday, because JOY.

Until tomorrow..